Aguafuerte Rosarina

I write to remember.

I write because I want to remember.

I write because I cannot remember.

I write because I should not forget.

I write because I forget.

I write to forget.

I write to cause something to survive.

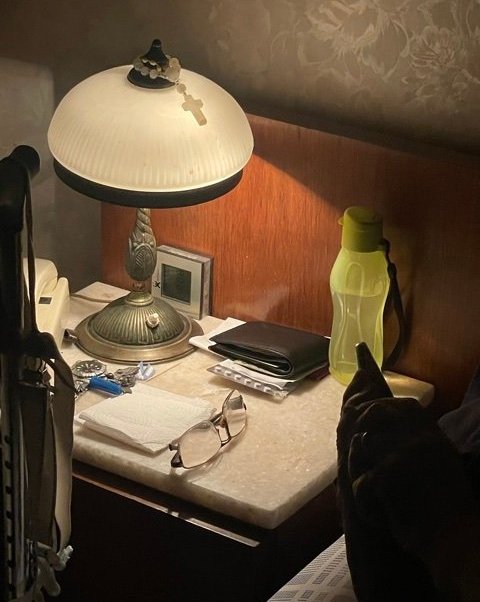

I'm staying at Paraguay al 400. My parents lived in this apartment before I was born. My father's consultancy, software before scale, worked out of here. After them, his brother stayed for a decade, until their second child outgrew the space. Now, the third brother. Each is seven years apart, naturally phasing their desires for the space. This last one, a former professional rugby player, is the chepibe. He's been staying with my weakened grandfather since the pandemic. The apartment is empty, so another generation slips in.

During meals with my grandfather we speak of Santa Maria de Oro and Leandro Alem... Mitre, San Martín, Sarmiento, empty signifiers devoid of history for me. Despite almost yearly visits as a child, I haven't been to Rosario half a decade. I've never lived in Argentina, yet these names flash me to childhood trips to my parents hometown, to living rooms, garage doors, and plates of food. Psychogeographical compressions.

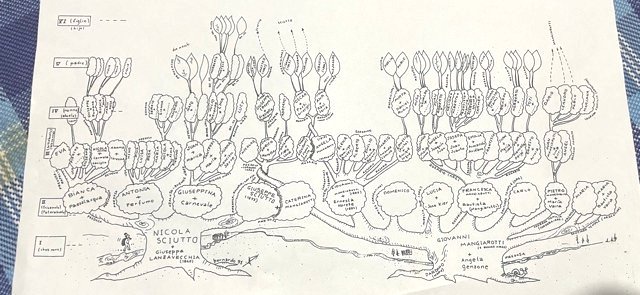

My father's family, the Mangiarotti (quelli che mangiano rotti?) and the Sciutto (deriva dal sostantivo Ligure 'sciutu' che in senso figurato si riferisce ad un individuo magro), arrived from Predosa, a town in the Italian Piedmont. Around three hundred kilometers upstream from their arrival in Buenos Aires was Rosario, la Chicago Argentina, and a sixty kilometers further Totoras and Serodino, small villages built among grain and livestock production. The first generation, Giuseppe Sciutto and Giovanni Mangiarotti stayed in the countryside. The next trickled back into the city for study, work, or health.

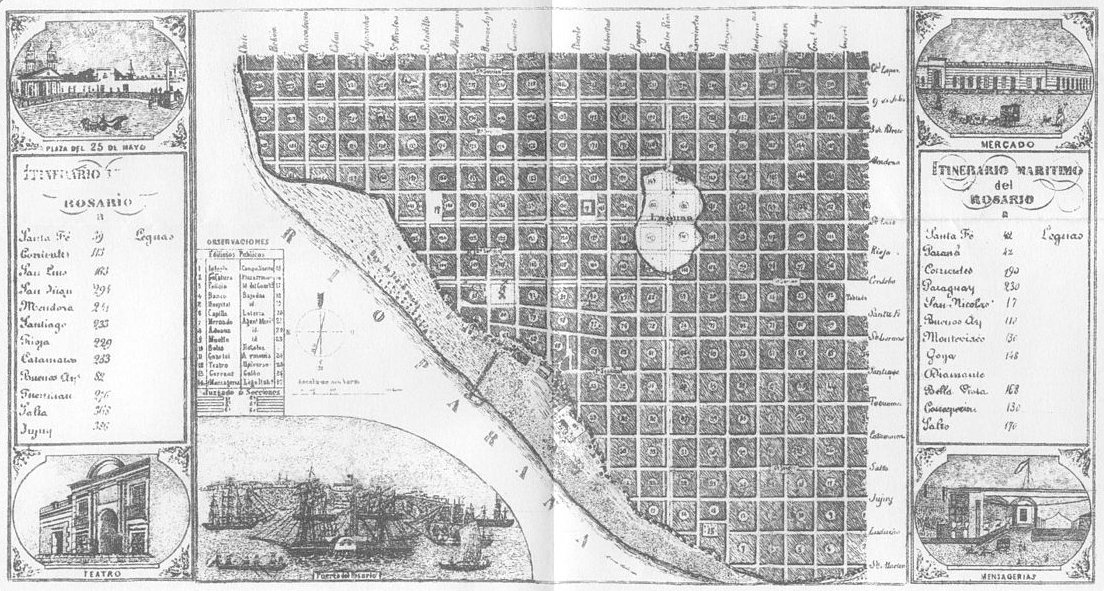

Nestled under a meander of the Parana river, Rosario forms a grid. Its Cartesian perfection transcends the orthogonality of Manhattan: each block measures 100 meters; the house number measures the distance to the origin. Unlike NYC, neighborhoods go unnnamed. Locations are named only through abscissas and ordinates. Paraguay al 400. Tucuman al 1800. My grandmother lives along the southern border, Ayacucho al 6100, just before Circunvalacíon, the ring road. Corrollary: the planned quadrant of the town is 36 kilometers squared. The city blocks are chamfered into octagons, reminiscent of another planned city, though this one is more lively. Near the origin is the national monument to the Argentine flag, Rosario's jewel, an austere marble boat pointing to the sea. My father would skip school to sail across the river and camp on the barrier islands.

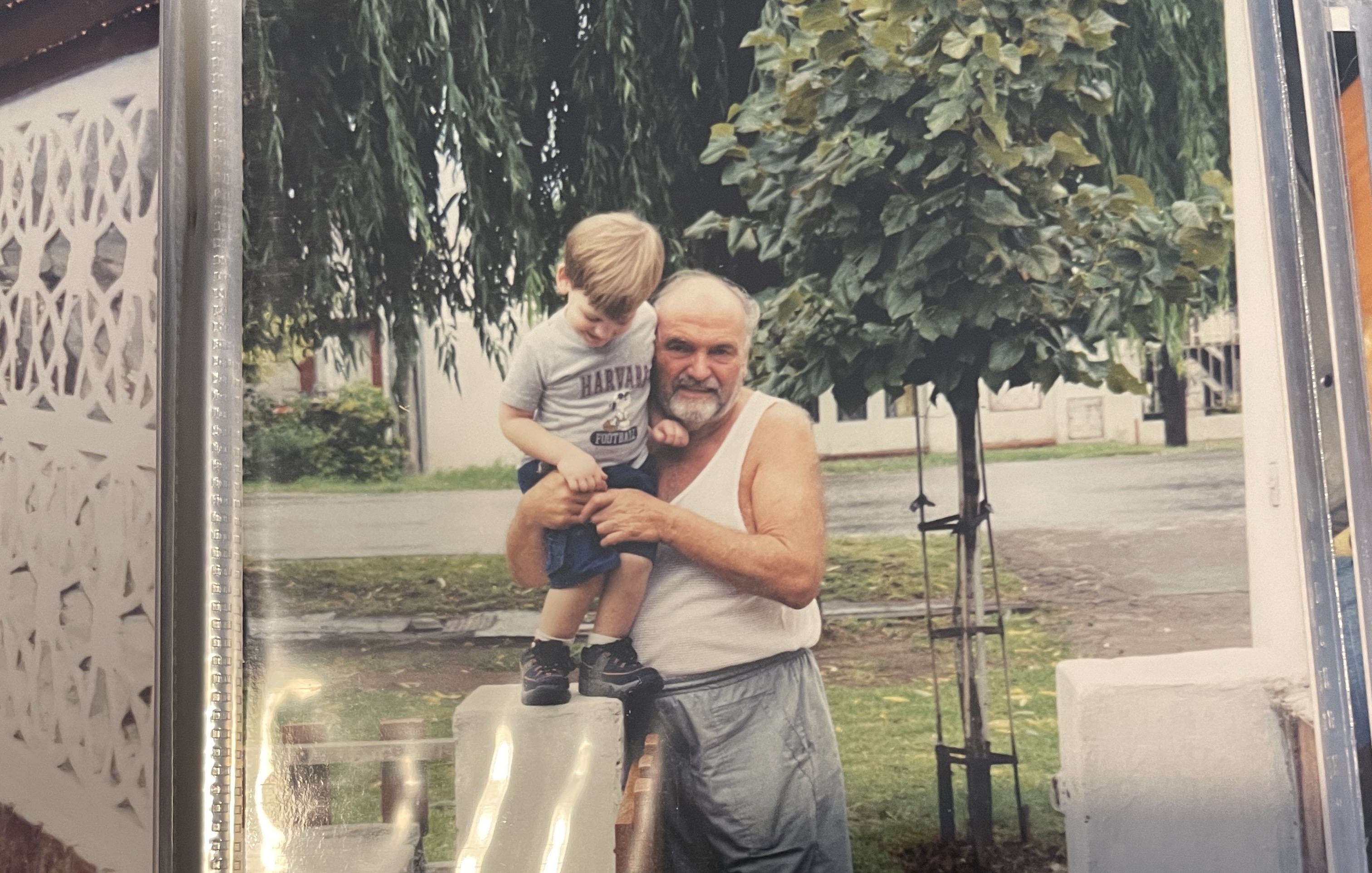

Despite the impersonal metric, the town is geographically split into local kinships. Every store is owned by the son of a neighbor. The lawyer is a school friend. The doctor, a member of the same recreational club. My father's family revolved around Santa Maria de Oro al 400, and later Alem al 2200. More accurately than Rosario, my father is first from Refineria, and then Republica de la Sexta. Moving brought along the whole family. Blocks away were Elena, Angelita, and Pocha, as well as Juan's corner store. Alberto and Emilio stayed in the countryside, though they moved into the nearby town of Serodino. My father was raised by an assembly of grandparents and aunts. Nothing more foreign to his child, who's never lived in the same country as anyone other than his mother and father.

I join my cousins in Zona Sur for an asado at my mother's mother—the Rodriguez. The broken tiles of terracotta making up the courtyard flooring and the cool bathroom with dusty yellow light filtering through the aged plastic ceiling aperture, form the kernel of my memories. It's an architectural transposition of the culinary maxim: all food is memory. Pictures of me are scattered throughout the house. When my mother left with my father for Peru, they sent yearly photo albums back. There's a whole bookshelf of them. That lasted for a decade or so, until the internet. Now, we just share less pictures.

My mother's father built the house before she was born. I'm told that as a kid I used to play in his workshop, entertaining myself with rusted nuts and bolts. He worked at la Jabonería Guereño for four decades and collected every edition of Reader's Digest. With his brother Cacho, he built a quincho on the margins of the river a short distance away, true anarchic appropriation of land, home of the dolce far niente. Three decades ago the barbecue would have been there. Space as a commons, no authorization, no permits.

We watch a World Cup match while sharing a mate, snacking on my grandmother's alfajores de maizena and pastaflora de membrillo. During half time, my little cousin Leonel challenges me at chess. His intuitions are better than mine, but he moves too quickly, a blunder. His older brother Valentín punishes him with patience. Valentín studies at the Politécnico, a bastion of technocratic public secondary education. Every first year student makes a wooden stool in wood shop. Once a year, during the taburetazo, "los polipibes" occupy the streets raising their wooden confections. Leonel avoided studying for the entrance exam. It was easy, he says, but he doesn't want to get in.

We drive nearby to Messi's childhood neighborhood, adjacent to the 121st Battalion. It's been converted to the Parque Heroés de Malvinas. Were my father two years older, he would've gone to war. Now, the city is divided into the fútbol rivals Rosario Central and Newell's Old Boys. Around us, the red and black of the latter dominates. I'm told of the dangers. "Wait for me inside the bus station," my uncle insisted. "I wouldn't walk around where your grandmother lives." Los Monos are at war with Los Garompas for ravioles de falopa. Google Los Monos and you'll see a bunch of Canallas. Fútbol and violence. On the news: A couple of kids gunned down while asking for payments at the búnkers. Esta banda quilombera no te deja, no te deja de alentar.

I walk around with four keys: key fob for the front door, backup key, top lock of apartment door, and bottom lock. Four more for my grandfather's. Same for my parent's rental. Near Calle Paraguay, everything feels safe. Streets buzz with taxis like an old New York City film. Step out and whistle. The literary stereotypes materialize with a bookstore nearly every block. The riverside is ostensibly public space. A large brick complex, Parque España, cradles into the incline. Its hundreds of stairs form a public auditorium to watch the sun wane over the river. And as everyone knows, las Rosarinas son las mas lindas del mundo. I meet my great-aunt Olga at Juan Manuel de Rosas y Pellegrini. "Esta ciudad es preciosa," I say, en Español sin las eses. She agrees, but no one seems to realize.

"De vez en cuando, hay que sincerarse," Olga suggests. Family tensions are high: unhealthy grandparents, uncles who won't talk to their nephews, brothers fighting over family duty. The real turmoil is within the family. Some seem to have committed sincericidio. Buenos Aires is a city, Rosario an overgrown village.

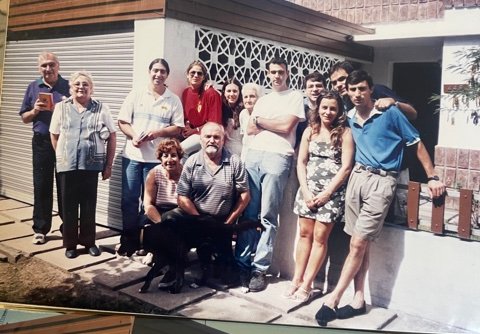

A second-cousin is in emergency care. More Rodriguez arrive from Pigüé and Punta Alta. I'm told Aira, from Coronel Pringles, best captures "los pueblos." We congregate at Menggano for four hours. Table for fourteen: Olga, el Negro, Pacho, Flor, Santiago y Nacho, Gonzalo, el Tribi, Patricia, Guillermo, Juli, Carina, Lisandro, and Cristóbal. Carlitos especial and cafes en jarritas are ordered by the dozen. I remember the lunch scene from È stata la mano di Dio. We pass a phone we've brought from the US to the cousins. Everyone hushes. Gonzalo tells us how Dario clenched his jaw upon seeing him, pissed at the situation, at being immobile. The same burst of consciousness happened with my father's mother, the opening of her eyes on his arrival. Familia es familia.

Cristóbal Sciutto, December 2022.